17th July, 2011

Nicole Rolet is living the dream. Specifically, she’s living my dream.

Owning a vineyard in a gorgeous, sunny location. Living in a centuries-old stunning house. Producing beautiful award-winning wines.

But hearing Nicole tell the story of getting Chêne Bleu wines up and running, it’s clear this hasn’t all been rainbows and unicorns.

Nicole and her husband Xavier didn’t set out to make wine at La Verrière, the run-down medieval priory in Provence Xavier bought in the 1990s. At most, they thought they’d revitalise the old vines surrounding the property and sell the grapes to one of the local wine co-ops.

However, after calling in top soil experts Claude and Lydia Bourguignon, who told them of the ” incredible potential” for vines, they changed their minds. Plans to kick back a little were put on hold as Xavier went back to work in order to raise more money for the venture (he is now CEO of the London Stock Exchange Group). Nicole – also a former banker – went to study wine.

Oak Couture

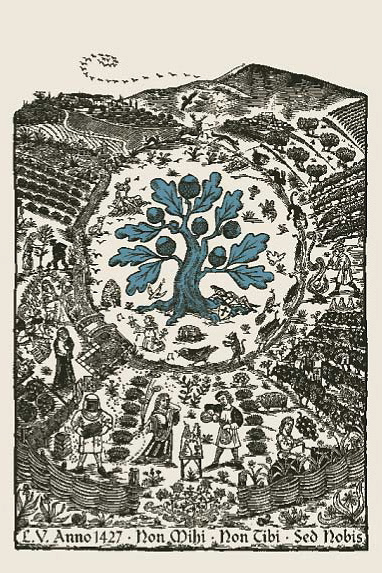

Today, they are producing what they describe as “couture” wines under the label Chêne Bleu – named after a gnarly old oak in the grounds which has been sculpted and treated with a blue solution to protect it.

They roped in Xavier’s sister Bénédicte Gallucci, a viticulturalist, and her husband Jean-Louis who makes the wines. They also secured advice from renowned oenologists such as Zelma Long, winemaker at Robert Mondavi for many years, Philippe Cambie and Doug Margerum.

Listening to Nicole talking at a Château Boundary event I was invited to, it would easy to dismiss all this as a vanity project by people who’d made their fortune in finance. For example, Chêne Bleu produces around 14-22 hectolitres of wine per hectare which Nicole says is “not very productive, but in exchange, we think the quality is quite exciting.”

They hand-sort individual grapes (not just bunches); use Medieval harvesting techniques in the vineyard; and divide vineyards into blocks, vinifying the grapes from each in separate tanks. “It’s a luxury to have as many tanks as we do,” admits Nicole.

But Xavier comes from a lineage of wine producers, and Nicole and team appear to be putting in a lot of hard graft to produce the very best wines they can, and promote them. You can see Nicole depicted in the beautifully-designed wine labels as the “chief plate spinner”.

Their big decisions over what wine to produce was primarily down to geology. The vineyard is 600 metres above sea level in the foothills of Mount Ventoux.

“Geology was really important to decide what we are doing,” says Nicole, adding that despite there being no topsoil, it’s a treasure trove of garrigue, schist and clay. “This gives a mineral signature throughout the wines which is why we think we can do something a bit different.”

Rhône Alone

Different is key here. Lying between four appellations (Côtes du Ventoux, Côtes du Rhône, Gigondas and Séguret), the natural assumption would be for a high-end wine producer like Chêne Bleu to make a product that follows strict French appellation rules for that added cachet. But the team was of the firm belief that this would produce an inferior product given the uniqueness of the natural resources.

“We were making better wine outside the appellation, so we opted for the Clint Eastwood approach to winemaking,” explains Nicole. Which means despite all the biodynamic, handcrafted principles, wines made by Chêne Bleu are classified as Vin de Pays.

Does this matter? To me, no. It’s all about the producer. Not everyone thinks this way though, particularly when your top wines retail for around £65.

These are the voluptuous, seductive Syrah-driven Héloïse and the spicy, brooding Grenache-dominated Abélard. We tried the 2006 vintage, the first release, which both won silver at the IWC in 2009. Chêne Bleu is calling these “super Rhônes”, after the super Tuscans of the 1990s – great wines that fell outside the Chianti classification rules.

Chêne Bleu also makes a very good Roussane, White Grenache and Marsanne blend called Aliot. The 2008 tasted of pears and jasmine with a lovely mineral streak. This won gold at the 2009 IWC.

We also tried the Viognier 2007, which had a wonderful heady smell of waxy, pungent honeysuckle but was aggressively oaked, stifling some of the stonefruit flavours underneath, though good with a pissaladière canapé.

Finally, there was the strawberry and slightly orangey-tasting rosé, made from Grenache and Syrah grown specifically for making rosé (rather than for red wine). According to Nicole, this wine appeals to the anti-rosé brigade. As someone who shies away from most of the tasteless, acidic offerings in the UK, I thought she was right. Especially when matched with cold pistou soup later at dinner later that evening.

Chêne Bleu wines are not cheap. They start at around £24 for the rosé. But we’re talking Jermyn Street here, not high street – a completely hand-crafted approach to making wine. Would I buy one of the reds at £65? Yes. Not for everyday drinking, but for an occasion or a present. Let’s face it, I can pay more for an inferior wine in a restaurant.

Despite Nicole’s assertion that they don’t have a particular market in mind I’m sure the reds will prove popular in two regions: the US and Asia. And among wine geeks like me who appreciate the care and attention that has gone into producing these wines.